First I'm going to make the cranks and planet gear assembly. These parts are the heart of this wonderful little machine. I've had a good long think about this assembly over recent months and I've planned the order of machining so that that everything fits properly, the gears line up, are correctly spaced and both sides are equidistant from the centre line. This isn't trivial as I'll try to illustrate over the next few weeks.

One of the things I still need to determine is how I'm going to attach my cranks to the live axle. This is another case where every example I have seen has used a different method. The original I am copying has both cranks screwed to the live axle and then locked in position with taper pins. Others I have seen use Renouf's patent wedge, modern cotter pins and taper pins with a split axle. I need to investigate taper pins to see if I can get hold of a suitable reamer. Taper pins were extensively used to secure collars and pulleys to shafts back in the day, properly made and installed, they do not come free. More later.

The first part is to make the adjustable bearing cones for the live axle and the planet gear.

When I measured and photographed the original bike I didn't realise that these are interchangeable and I diligently measured each one separately. These will be made from 4140 chromoly and nitrided as with all the other bearing surfaces. As usual here is a pictorial list of the various machining processes to make them.

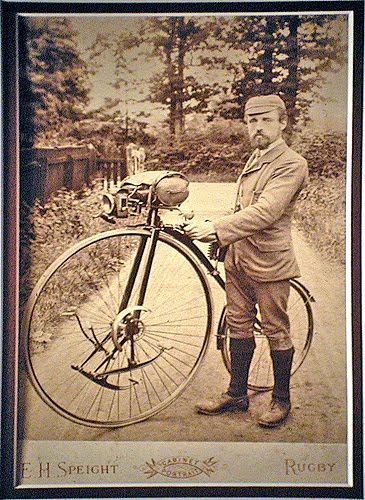

It's his fault that I've ended up like this.

I used a collet chuck for this so I could ensure easy concentricity when taken off and remounted on the dividing head.

I only have two collets, I wish I had a full imperial set, they are jolly useful.

Using the same highly contrived setup as before when machining the locking slots.

In other news, work on my lovely wife's deck is progressing. I've called in a few favours this weekend to get the post holes dug. I simply can't do hard manual digging any more, my back lets me know very firmly that it is not happy and it wants me to stop. Unfortunately the rain has been persisting down again and work has had to stop. We got 11 out of the 15 holes dug, these are now full of water and dangerously hidden. The deluge has caused a lot of damage locally and nationally and one landslip proved fatal when it destroyed a house. My lovely wife failed to get to work as the flood has removed a necessary bridge and I've restricted myself to riding the motorbike in daylight hours as many roads are flooded and unlit. We are due for an Antarctic blast later this week. If it snows and I can't get to work I'll be forced to work from home <cough> shed </cough>.

Also, Tweed Pete's new saddle is coming along, I've worked out a quicker method of making the laminated wooden block. Pete has lots of useful contacts and I recently had a riveting conversation with him. I've run out of genuine Brooks rivets so I needed a local supply. I gave Pete the important dimensions and asked him to see what he could do.